Quantum physics, Religion and Buddhism

Religion may be defined as a cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that relates humanity to supernatural, transcendental, or spiritual elements. However, there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.

In a sense, Buddhism seems like a religion. However Buddhism embraces both religion and science.

So I will present two main sections:

The appearance of the Dalai Lama: Religion Without Quantum Physics Is an Incomplete Picture of Reality

“Broadly speaking, although there are some differences, I think Buddhist philosophy and Quantum Mechanics can shake hands on their view of the world. We can see in these great examples the fruits of human thinking. Regardless of the admiration we feel for these great thinkers, we should not lose sight of the fact that they were human beings just as we are.” – The Dalai Lama

For a long time, science and spirituality were considered to be opposing views, creating this polarization of both subjects. You were either a “Man of God” or a “Man of Science,” with no middle ground. However, we’re now observing a merging of both science and spirituality through quantum physics and the study of consciousness, shattering old thought patterns and putting an end to the previous “tug of war” between the two subjects.

So how does quantum reality fit with Buddhist Philosophy?

The two aspects of Buddhist philosophy that are relevant to observations at the quantum level are The Four Seals of Dharma and the Three Modes of Existential Dependence. These teachings were established centuries ago, long before modern physics evolved, and were derived from careful philosophical and meditational analysis of the world. However their description of quantum reality is remarkably accurate, as they predicted that:

(1) Particles are not inherently existent. No particle is 'a thing in itself' with a self-contained identity. An inherently-existent particle would be indestructible, unitary and indivisible.

(2) Particles are not causeless.

(3) Particles are not partless, they do not exist as indivisible points.

(4) Particles are not 'permanent' in the sense of having a unchanging, static identity.

(5) Particles exist by interaction with the mind of an observer.

...and what we actually see is...

(1) Particles cannot function as stand-alone entities. They can only interact with the rest of the universe by exchanging something of themselves - for example gluons or photons. Their properties can only be known by their interactions with other particles, and thus cannot be completely accurately established.

(2) Particles are brought into existence by energetic events. The mother of all energetic events was the Big Bang, which brought most of the existing particles into existence. But natural energetic events such as cosmic rays and beta decay continue to produce particles, and energetic man-made events in particle accelerators produce secondary particles by hadronization and creation of particle-antiparticle pairs.

(3) The tiniest particles (quarks and leptons) do not have parts because they are physically indivisible, but according to the Madhyamika school they have directional parts and so are mentally divisible. If even these smallest forms have parts, it follows that all gross forms that are composed of them also have parts. - Ocean of Nectar p 164

But if, according to Buddhist philosophy, partless particles cannot exist, how can we avoid the infinite regress of small building-blocks being composed of even smaller building-blocks, all the way down for ever?

This infinite regress...

In a sense, Buddhism seems like a religion. However Buddhism embraces both religion and science.

So I will present two main sections:

- Quantum physics and Religion

- Quantum physics and Buddhism

1. Quantum physics and Religion

#Quantum physics religion philosophy

In the early 1970s New Age culture began to incorporate ideas from quantum physics, beginning with books by Arthur Koestler, Lawrence LeShan, and others which suggested that purported parapsychological phenomena could be explained by quantum mechanics. In this decade the Fundamental Fysiks Group emerged, a group of physicists who embraced quantum mysticism while engaging in parapsychology, Transcendental Meditation, and various New Age and Eastern mysticalpractices. Inspired in part by Wigner, Fritjof Capra, a member of the Fundamental Fysiks Group, wrote The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels Between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism (1975), a book espousing New Age quantum physics that gained popularity among the non-scientific public. In 1979 came the publication of The Dancing Wu Li Masters by Gary Zukav, a non-scientist and "the most successful of Capra's followers". The Fundamental Fysiks Group is said to be one of the agents responsible for the "huge amount of pseudoscientific nonsense" surrounding interpretations of quantum mechanics.

“Broadly speaking, although there are some differences, I think Buddhist philosophy and Quantum Mechanics can shake hands on their view of the world. We can see in these great examples the fruits of human thinking. Regardless of the admiration we feel for these great thinkers, we should not lose sight of the fact that they were human beings just as we are.” – The Dalai Lama

For a long time, science and spirituality were considered to be opposing views, creating this polarization of both subjects. You were either a “Man of God” or a “Man of Science,” with no middle ground. However, we’re now observing a merging of both science and spirituality through quantum physics and the study of consciousness, shattering old thought patterns and putting an end to the previous “tug of war” between the two subjects.

#Quantum physics and Eastern Religion

Eastern philosophy or Asian philosophy includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asiaincluding Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, and Korean philosophy which are dominant in East Asia and Vietnam, and Indian philosophy (including Buddhist philosophy) which are dominant in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Tibet and Mongolia.

All the interferences of Eastern philosophy and modern Physics are clearly reflected in the book The Tao of Physics

The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels Between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism is a 1975 book by physicist Fritjof Capra. It was a bestseller in the United States and has been published in 43 editions in 23 languages. The fourth edition in English was published in 2000.

The following excerpt from The Tao of Physics summarizes Capra's motivation for writing this book

“Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science. But man needs both.”

According to the preface of the first edition, reprinted in subsequent editions, Capra struggled to reconcile theoretical physics and Eastern mysticism and was at first "helped on my way by 'power plants'" or psychedelics, with the first experience "so overwhelming that I burst into tears, at the same time, not unlike Castaneda, pouring out my impressions to a piece of paper". (p. 12, 4th ed.)

Capra later discussed his ideas with Werner Heisenberg in 1972, as he mentioned in the following interview excerpt:

As a result of those influences, Bohr adopted the yin yang symbol as part of his family coat of arms when he was knighted in 1947.

The Tao of Physics was followed by other books of the same genre like The Hidden Connection, The Turning Point and The Web of Life in which Capra extended the argument of how Eastern mysticism and scientific findings of today relate, and how Eastern mysticism might also have answers to some of the biggest scientific challenges of today.

2. Quantum physics and Buddhism

Convergence of Physics with Buddhist Philosophy

One of the interesting aspects of quantum physics from the Buddhist point of view is that particles, which in classical physics were once regarded as little pieces of matter, are now regarded as processes consisting of continuously evolving and changing wavefunctions. These processes only give the appearance of discrete and localized particles at the moment they are observed.

So particles are forever changing, and lack any inherent existence independent of the act of observation. Consequently, everything composed of particles is also impermanent and continually changing, and no static, stable basis for its existence can be found.

Therefore, at a very generalized level, the scientific view of the world has converged with the Buddhist view. Buddhism is a 'process philosophy', holding that the underlying basis of reality is change, process and impermanence. Becoming is more basic than being, and existence is really just impermanence in slow-motion.

The converse view is substantialism, which holds that constant realities or substances underlie phenomena. In the transition from classical to modern physics, atomic theory has changed from substantialism to being in agreement with the Buddhist process view of reality.

Furthermore, when we look at the interaction of the wave-particles with the observer, we find additional interesting correspondences between Buddhist philosophy and quantum physics, as discussed below:

The observer is part of the system

The strange interactions of fundamental particles with the mind of the observer ('quantum weirdness') have long been of interest to philosophers. There are two opposing views: (i) Quantum weirdness produces the mind, versus (ii) The mind produces quantum weirdness.

(i) Quantum weirdness produces the mind

Materialist philosophers have suggested that quantum weirdness offers a means of filling the explanatory gap (known as 'The Hard Problem') between the machine-like neurological functions of the brain, and the subjective sensations of the mind such asqualitative experience and 'aboutness'.

Materialists claim that quantum effects offer a way of generating non-mechanistic mental activity from a purely physical basis. These suggestions have met with a number of objections, and don't seem to have the explanatory power to fill the gap. (see The Penrose-Hameroff Conjecture later in this article).

(ii) The Mind produces quantum weirdness

In contrast, Buddhist philosophers claim the mind is a fundamental aspect of reality, which is 'axiomatic', in the sense of not being reducible to a physical basis, such as to the physico-chemical activities in the brain.

Buddhists regard the mind as a primary fact of reality, like space-time, in which we live, and move, and have our being. This axiomatic mind cannot be reduced to other facts. It is implicit and foundational in all facts and in all knowledge.

Mind is clear and cognizing, and for Buddhists is the basis on which all other explanations rest, and is one of the three foundations of functioning phenomena (the other two being causality and structure).

One of the interesting aspects of quantum physics from the Buddhist point of view is that particles, which in classical physics were once regarded as little pieces of matter, are now regarded as processes consisting of continuously evolving and changing wavefunctions. These processes only give the appearance of discrete and localized particles at the moment they are observed.

So particles are forever changing, and lack any inherent existence independent of the act of observation. Consequently, everything composed of particles is also impermanent and continually changing, and no static, stable basis for its existence can be found.

Therefore, at a very generalized level, the scientific view of the world has converged with the Buddhist view. Buddhism is a 'process philosophy', holding that the underlying basis of reality is change, process and impermanence. Becoming is more basic than being, and existence is really just impermanence in slow-motion.

The converse view is substantialism, which holds that constant realities or substances underlie phenomena. In the transition from classical to modern physics, atomic theory has changed from substantialism to being in agreement with the Buddhist process view of reality.

Furthermore, when we look at the interaction of the wave-particles with the observer, we find additional interesting correspondences between Buddhist philosophy and quantum physics, as discussed below:

The observer is part of the system

The strange interactions of fundamental particles with the mind of the observer ('quantum weirdness') have long been of interest to philosophers. There are two opposing views: (i) Quantum weirdness produces the mind, versus (ii) The mind produces quantum weirdness.

(i) Quantum weirdness produces the mind

Materialist philosophers have suggested that quantum weirdness offers a means of filling the explanatory gap (known as 'The Hard Problem') between the machine-like neurological functions of the brain, and the subjective sensations of the mind such asqualitative experience and 'aboutness'.

Materialists claim that quantum effects offer a way of generating non-mechanistic mental activity from a purely physical basis. These suggestions have met with a number of objections, and don't seem to have the explanatory power to fill the gap. (see The Penrose-Hameroff Conjecture later in this article).

(ii) The Mind produces quantum weirdness

In contrast, Buddhist philosophers claim the mind is a fundamental aspect of reality, which is 'axiomatic', in the sense of not being reducible to a physical basis, such as to the physico-chemical activities in the brain.

Buddhists regard the mind as a primary fact of reality, like space-time, in which we live, and move, and have our being. This axiomatic mind cannot be reduced to other facts. It is implicit and foundational in all facts and in all knowledge.

Mind is clear and cognizing, and for Buddhists is the basis on which all other explanations rest, and is one of the three foundations of functioning phenomena (the other two being causality and structure).

So where does the weirdness come from?

For Buddhists, the freakiness at the smallest scale of physics is the result of our realisation of our mind's involvement in producing reality - that 'the observer is part of the system'.

This mental involvement is actually also apparent on careful examination at our everyday scale of reality, but we don't think about it unless it is painstakingly pointed out, as with King Milinda's chariot.

However, when we look at the very foundations of reality, the involvement of the observer's mind becomes inescapably obvious. The act of observation turns potentiality into actuality.

Observation resolves the question of what the particle actually "is" through a combination of the particle's inherent potentials and the manner in which it is observed. For a discussion of the experimental details of mind/matter interactions seeQuantum Buddhism.

For Buddhists, the freakiness at the smallest scale of physics is the result of our realisation of our mind's involvement in producing reality - that 'the observer is part of the system'.

This mental involvement is actually also apparent on careful examination at our everyday scale of reality, but we don't think about it unless it is painstakingly pointed out, as with King Milinda's chariot.

However, when we look at the very foundations of reality, the involvement of the observer's mind becomes inescapably obvious. The act of observation turns potentiality into actuality.

Observation resolves the question of what the particle actually "is" through a combination of the particle's inherent potentials and the manner in which it is observed. For a discussion of the experimental details of mind/matter interactions seeQuantum Buddhism.

So how does quantum reality fit with Buddhist Philosophy?

The two aspects of Buddhist philosophy that are relevant to observations at the quantum level are The Four Seals of Dharma and the Three Modes of Existential Dependence. These teachings were established centuries ago, long before modern physics evolved, and were derived from careful philosophical and meditational analysis of the world. However their description of quantum reality is remarkably accurate, as they predicted that:

(1) Particles are not inherently existent. No particle is 'a thing in itself' with a self-contained identity. An inherently-existent particle would be indestructible, unitary and indivisible.

(2) Particles are not causeless.

(3) Particles are not partless, they do not exist as indivisible points.

(4) Particles are not 'permanent' in the sense of having a unchanging, static identity.

(5) Particles exist by interaction with the mind of an observer.

...and what we actually see is...

(1) Particles cannot function as stand-alone entities. They can only interact with the rest of the universe by exchanging something of themselves - for example gluons or photons. Their properties can only be known by their interactions with other particles, and thus cannot be completely accurately established.

(2) Particles are brought into existence by energetic events. The mother of all energetic events was the Big Bang, which brought most of the existing particles into existence. But natural energetic events such as cosmic rays and beta decay continue to produce particles, and energetic man-made events in particle accelerators produce secondary particles by hadronization and creation of particle-antiparticle pairs.

(3) The tiniest particles (quarks and leptons) do not have parts because they are physically indivisible, but according to the Madhyamika school they have directional parts and so are mentally divisible. If even these smallest forms have parts, it follows that all gross forms that are composed of them also have parts. - Ocean of Nectar p 164

But if, according to Buddhist philosophy, partless particles cannot exist, how can we avoid the infinite regress of small building-blocks being composed of even smaller building-blocks, all the way down for ever?

This infinite regress...

... doesn't happen with the building blocks of matter

The resolution of this apparent contradiction came with discoveries in quantum physics in the early twentieth century. When physicists arrived at the stage where further subdivision was no longer possible, they did indeed find numerically irreducible particles. However these particles are no longer discrete 'things', but are smeared out into a myriad of fuzzy probabilistic 'parts' - a continuum of probabilities distributed in a wave function with spatial 'directional parts'.

And they can even be in two places at once.

(4) All particles show 'subtle impermanence' - they do not remain in exactly the same state from one moment to the next. In the nucleus, protons and neutrons are constantly exchanging mesons to hold themselves together.

In the outer layers of atoms the electrons are never at a single location in their orbitals, but vibrate like a standing wave on a string

(5) The act of observation turns potentiality into actuality, resolving the question of what the particle actually "is" through a combination of the particle's inherent potentials and the manner in which it is observed.

The mathematical equations of quantum physics do not describe actual existence - they predict the potential for existence. Working out the equations of quantum mechanics for a system composed of fundamental particles produces a range of potential locations, values and attributes of the particles which evolve and change with time. But for any system only one of these potential states can become real, and - this is the revolutionary finding of quantum physics - what forces the range of the potentials to assume one value is the act of observation.

Matter and energy are not in themselves phenomena, and do not become phenomena until they are observed. For a discussion of the experimental details see Quantum Buddhism.

In the outer layers of atoms the electrons are never at a single location in their orbitals, but vibrate like a standing wave on a string

(5) The act of observation turns potentiality into actuality, resolving the question of what the particle actually "is" through a combination of the particle's inherent potentials and the manner in which it is observed.

The mathematical equations of quantum physics do not describe actual existence - they predict the potential for existence. Working out the equations of quantum mechanics for a system composed of fundamental particles produces a range of potential locations, values and attributes of the particles which evolve and change with time. But for any system only one of these potential states can become real, and - this is the revolutionary finding of quantum physics - what forces the range of the potentials to assume one value is the act of observation.

Matter and energy are not in themselves phenomena, and do not become phenomena until they are observed. For a discussion of the experimental details see Quantum Buddhism.

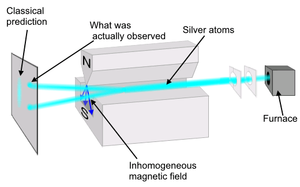

Triple slit experiment

From Nature

'If you ever want to get your head around the riddle that is quantum mechanics, look no further than the double-slit experiment. This shows, with perfect simplicity, how just watching a wave or a particle can change its behaviour. The idea is so unpalatable to physicists that they have spent decades trying to find new ways to test it. The latest such attempt, by physicists in Europe and Canada, used a three-slit version — but quantum mechanics won out again... Full article

'If you ever want to get your head around the riddle that is quantum mechanics, look no further than the double-slit experiment. This shows, with perfect simplicity, how just watching a wave or a particle can change its behaviour. The idea is so unpalatable to physicists that they have spent decades trying to find new ways to test it. The latest such attempt, by physicists in Europe and Canada, used a three-slit version — but quantum mechanics won out again... Full article

The Penrose-Hameroff Conjecture

From http://philosophy.uwaterloo.ca/MindDict/quantum.html

Penrose's main argumentative line can be summed up as follows:

Part A: Nonalgorithmicity of human conscious thought.

A1) Human thought, at least in some instances, is sound , yet nonalgorithmic (i.e. noncomputational). (Hypothesis based on the Gödel result.)

A2) In these instances, the human thinker is aware of or conscious of the contents of these thoughts.

A3) The only recognized instances of nonalgorithmic processes in the universe are perhaps certain kinds of randomness; e.g. the reduction of the quantum mechanical state vector. (Based on accepted physical theories.)

A4) Randomness is not promising as the source of the nonalgorithmicity needed to account for (1). (Otherwise mathematical understanding would be magical.)

Therefore:

A5) Conscious human thought, at least in some cases, perhaps in all cases, relies on principles which are beyond current physical understanding, though not in principle beyond any (e.g. some future) scientific physical understanding. (Via A1 - A4)

Part B: Inadequacy of Current Physical Theory, and How to Fix It.

B1) There is no current adequate theory concerning the 'collapse' of the quantum mechanical wave function, but an additional theory of quantum gravity might be useful to this end.

B2) A more adequate theory of wave function collapse (a part, perhaps, of a quantum gravity theory) could incorporate nonalgorithmic, yet nonrandom, processes. (Penrose hypothesis.)

B3) The existence of quasicrystals is evidence for some such currently unrecognized, nonalgorithmic physical process.

Therefore:

B4) Future theories of physics, in particular quantum gravity, can be expected to incorporate nonalgorithmic processes. (via B1 - B3)

Part C: Microtubules as the means of harnessing quantum gravity.

C1) Microtubules have properties which make certain quantum mechanical phenomena (e.g. super-radiance) possible. (Hameroff/Penrose hypothesis.)

C2) These nonalgorithmic nonrandom processes will be sufficient, in some sense, to account for A5. (Penrose hypothesis.)

C3) Microtubules play a key role in neuron function.

C4) Neurons play a key role in cognition and consciousness.

C5) Microtubules play a key role in consciousness/cognition (by C3, C4 and transitivity).

Therefore:

C6) Microtubules, because they have one foot in quantum mechanics and the other in conscious thought, provide a window for nonalgorithmicity in human cognition.

Conclusion:

D) Quantum gravity, or something similar,via microtubules, must play a key role in consciousness and cognition.

From http://philosophy.uwaterloo.ca/MindDict/quantum.html

Penrose's main argumentative line can be summed up as follows:

Part A: Nonalgorithmicity of human conscious thought.

A1) Human thought, at least in some instances, is sound , yet nonalgorithmic (i.e. noncomputational). (Hypothesis based on the Gödel result.)

A2) In these instances, the human thinker is aware of or conscious of the contents of these thoughts.

A3) The only recognized instances of nonalgorithmic processes in the universe are perhaps certain kinds of randomness; e.g. the reduction of the quantum mechanical state vector. (Based on accepted physical theories.)

A4) Randomness is not promising as the source of the nonalgorithmicity needed to account for (1). (Otherwise mathematical understanding would be magical.)

Therefore:

A5) Conscious human thought, at least in some cases, perhaps in all cases, relies on principles which are beyond current physical understanding, though not in principle beyond any (e.g. some future) scientific physical understanding. (Via A1 - A4)

Part B: Inadequacy of Current Physical Theory, and How to Fix It.

B1) There is no current adequate theory concerning the 'collapse' of the quantum mechanical wave function, but an additional theory of quantum gravity might be useful to this end.

B2) A more adequate theory of wave function collapse (a part, perhaps, of a quantum gravity theory) could incorporate nonalgorithmic, yet nonrandom, processes. (Penrose hypothesis.)

B3) The existence of quasicrystals is evidence for some such currently unrecognized, nonalgorithmic physical process.

Therefore:

B4) Future theories of physics, in particular quantum gravity, can be expected to incorporate nonalgorithmic processes. (via B1 - B3)

Part C: Microtubules as the means of harnessing quantum gravity.

C1) Microtubules have properties which make certain quantum mechanical phenomena (e.g. super-radiance) possible. (Hameroff/Penrose hypothesis.)

C2) These nonalgorithmic nonrandom processes will be sufficient, in some sense, to account for A5. (Penrose hypothesis.)

C3) Microtubules play a key role in neuron function.

C4) Neurons play a key role in cognition and consciousness.

C5) Microtubules play a key role in consciousness/cognition (by C3, C4 and transitivity).

Therefore:

C6) Microtubules, because they have one foot in quantum mechanics and the other in conscious thought, provide a window for nonalgorithmicity in human cognition.

Conclusion:

D) Quantum gravity, or something similar,via microtubules, must play a key role in consciousness and cognition.

Post a Comment